The History and Evolution of Insulin: From Leonard Thompson to Modern Diabetes Management

In December 1921, 14-year-old Leonard Thompson was on the brink of death. Suffering from diabetes and weighing only 65 pounds, his condition showed no improvement after a month at Toronto General Hospital. Desperate, doctors turned to an experimental treatment being developed by Canadian researchers.

In January 1922, Thompson was cautiously injected with a pancreatic extract derived from cows. At the time, the scientific understanding of diabetes was limited, but rapidly progressing. The medical team hoped that the extract, obtained from a healthy pancreas, would regulate blood sugar—a substance they called insulin.

The injection proved life-saving for Thompson, marking a turning point in the treatment of a condition that was previously considered a death sentence, according to the American Chemical Society (ACS).

Diabetes and Insulin Function

Diabetes is a chronic disease that disrupts the body’s glucose metabolism. High blood sugar usually signals the pancreas to release insulin. In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas produces little or no insulin, while in type 2, the pancreas may produce insulin, but the body cannot use it effectively. Both cases lead to elevated glucose levels, potentially causing serious complications in the circulatory, nervous, and immune systems, such as blindness, kidney failure, heart disease, or stroke.

Despite progress since Thompson’s time, diabetes remains the ninth leading cause of death worldwide, causing 1.5 million deaths in 2019. The global burden has risen dramatically, from 108 million cases in 1980 to 422 million in 2014, according to the World Health Organization. For those with access to insulin, diabetes is now largely manageable.

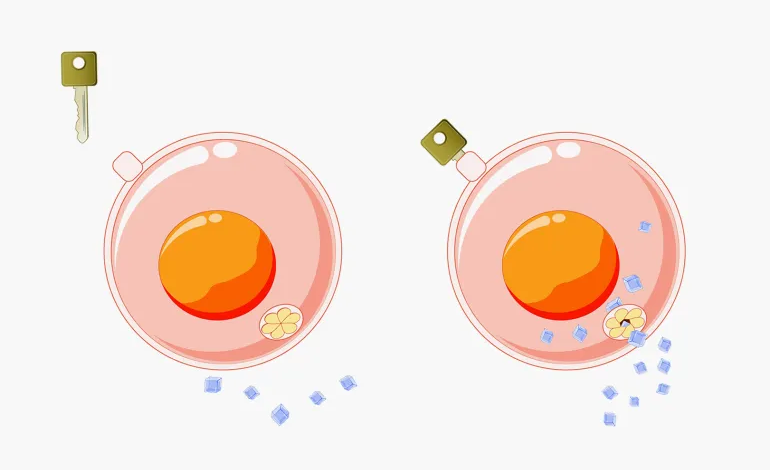

Insulin regulates blood glucose by binding to cell surface receptors, triggering structural changes that allow cells to absorb more glucose, thereby lowering circulating blood sugar levels. Insulin injections for diabetes replenish this hormone when the body cannot produce enough naturally.

Early History of Diabetes

The first recorded observations of diabetes date back 3,500 years to an Egyptian papyrus, where physician Hesy-Ra documented excessive urination. In 1675, British physician Thomas Willis identified the sweet taste of patients’ urine as a diagnostic clue.

In 1869, German medical student Paul Langerhans discovered clusters of pancreatic cells, later known as islets of Langerhans, whose function was initially unknown. Decades later, researchers found that removing the pancreas in dogs caused diabetes, suggesting the pancreas produced a substance necessary for sugar metabolism.

The term insulin, derived from the Latin word for “island,” was introduced in 1909, referencing the pancreatic islets. Early evidence showed these cells were destroyed in type 1 diabetes patients. Romanian physiologist Nicolae Paulescu demonstrated in 1916 that pancreatic extracts could lower blood sugar in diabetic dogs. However, early attempts to isolate insulin were often unsuccessful due to contamination or destruction of the active ingredient.

Frederick Banting and the Discovery of Insulin

Canadian physician Frederick Banting began his experiments in 1921, collaborating with Charles Best and James Collip under the guidance of University of Toronto physiology professor John Macleod. The team developed a method to extract and purify insulin from pancreatic cells, using alcohol to selectively dissolve insulin while separating impurities.

After successful animal tests, the first human trial was conducted on Leonard Thompson in January 1922, dramatically lowering his blood sugar and saving his life. Production techniques were refined, and by May 1922, Eli Lilly & Co. partnered with the university to scale up insulin manufacturing, shipping the first batches for clinical trials by July.

The Evolution of Insulin Therapy

Insulin quickly transformed diabetes from a fatal disease into a manageable condition. Early patients, like Thompson and Elizabeth Hughes, lived much longer due to regular insulin therapy. In 1923, Banting and Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize for the discovery of insulin.

Mass production of animal-derived insulin began soon after, with companies like Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Hoechst AG contributing. Early purification methods significantly impacted patient outcomes, as purity determined effectiveness and safety. By the 1930s-1950s, advances identified insulin as a single protein and sequenced its amino acids, laying the foundation for modern biochemistry and insulin production.

Recombinant Human Insulin

With biotechnology advances in the 1980s, companies developed recombinant human insulin using genetically engineered bacteria. The FDA approved Humulin in 1982, achieving 98% purity. This innovation allowed precise control over insulin structure and production, minimizing allergic reactions associated with animal-derived insulin.

Researchers then began developing insulin analogs, modifying amino acid sequences to adjust absorption, duration, and effectiveness. Rapid-acting analogs like Lispro and Aspart quickly become available for post-meal glucose control, while long-acting analogs like Degludec and Glargine provide steady basal insulin levels. These modifications help maintain optimal glucose levels while minimizing hypoglycemia risk.

Modern Diabetes Management

Today, insulin is available in multiple forms tailored to individual needs. Rapid-acting insulins provide quick glucose control, while long-acting insulins ensure stable levels over 24 hours. Researchers continue exploring innovative delivery systems, including microneedles and smart devices, to improve dosing precision and patient outcomes.

From Leonard Thompson’s first injection to recombinant insulin and engineered analogs, the journey of insulin exemplifies the evolution of medical science, saving millions of lives and continually advancing diabetes care.