European Migrant Detention Centers: Between Security and Human Rights

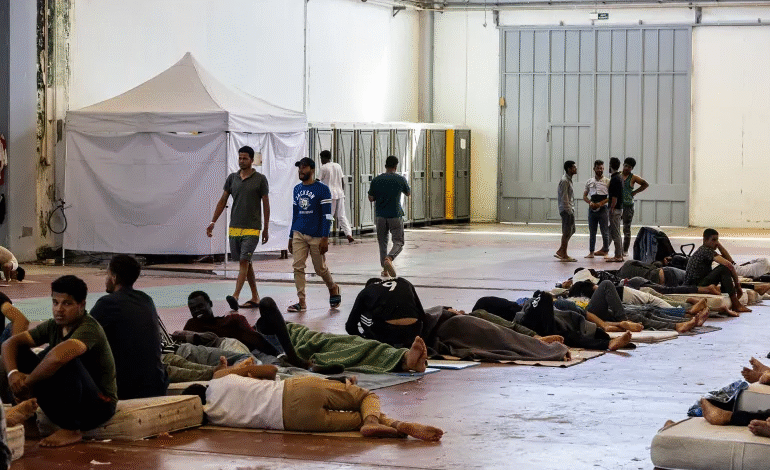

In remote and largely unseen areas of Europe, there exist isolated migrant detention centers that receive little media attention and are rarely included in official government reports. Thousands of individuals live there under conditions resembling prisons more than shelters.

Behind barbed wire and fences, security policies intersect with the fates of people fleeing danger, raising serious questions about transparency, human rights protection, and the limits of what Europe seeks to conceal from the world.

Forced Detention: Prison Without Trial

Although European laws do not label migrant detention centers as prisons, in practice they deprive individuals of freedom for varying periods, while limiting access to lawyers and essential information regarding their cases.

The 2025 report by the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA) highlighted a tightening of asylum procedures in EU countries with the implementation of the Migration and Asylum Pact, including the expansion of administrative detention measures not formally included in standard legal frameworks. The report offers a comprehensive overview of reception procedures, operational methods, and areas of rights-related tension in 2024 and 2025, emphasizing the urgent need for practical safeguards that allow asylum seekers to appeal refusals and access legal advice within detention facilities. Meanwhile, EU institutions continue to advance legislation prioritizing removal over protection.

On March 11, 2025, Reuters revealed a proposal to establish detention centers for rejected asylum seekers awaiting deportation, allowing individuals deemed security risks to be held for up to two years—a measure criticized by human rights organizations as a prescription for prolonged detention and undermining fairness standards.

Rejection decisions can quickly lead to extended detention, often accompanied by pressure to accept “voluntary return” or deportation to countries that may not offer adequate safety. Amnesty International warned that the notion of “repeated rejection” could expand detention duration on broad grounds, reduce genuine voluntary return options, and create a continuous penal system for non-cooperation with deportation procedures—indicating the absence of fair trial guarantees.

Psychological and social burdens multiply amid lack of information, lengthy procedures, and fear of deportation, especially when individuals are held in closed facilities without legal support, as documented in January 2025 investigations into EU-funded “voluntary return” projects in Bulgaria, which targeted individuals in detention, raising questions about the true voluntariness of such programs.

Reports from Amnesty International and the EUAA emphasize the urgent need for transparent standards in detention centers, including clear rules on detainees’ rights, independent complaint channels, and effective guarantees for legal and family communication.

Meanwhile, Frontex data from July 10, 2025, showed a 20% drop in irregular crossings during the first half of the year, weakening the argument of “exceptional pressure” and calling into question the political, ethical, and legal justification for expanding detention powers amid declining migrant numbers.

Media and Parliamentary Divisions

European detention centers form a complex network, with no comprehensive official map of their locations. However, a combination of official reports, monitoring, and investigative journalism has helped approximate the reality, which resembles temporary detention camps.

The EUAA’s evaluation focuses on reception and procedural practices, highlighting disparities between countries, particularly those facing high migrant inflows. The report notes “fast-track” and “border procedures” that detain individuals until decisions on their applications are finalized, often in remote facilities with limited media and parliamentary oversight, increasing the risk of fundamental rights violations, including restricted access to lawyers, limited healthcare, and difficulty communicating with the outside world.

The European Parliament witnessed heated debates over proposals to standardize removal decisions and establish centers outside the EU for rejected asylum seekers awaiting deportation. Media coverage reflected clear divisions: some viewed the measures as “restoring control,” while others warned of the risks of prolonged detention that contradict the principle of voluntary return.

Bulgaria serves as a notable example. During a June 2025 visit, the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture assessed centers including Busmantsi and Lyubimets, as well as border police facilities in Elhovo and Svilengrad, reporting conditions “equal to or worse” than those documented in 2018 in terms of food, activities, healthcare, legal information, and communication with the outside world.

Samos Center: A Case Study

In Greece, the Samos center exemplifies detention under the guise of “border procedures.” Its closed infrastructure intersects with fast-track processes, with multiple checkpoints, mandatory attendance schedules, and shifting administrative authority between asylum offices and police.

Although officially classified as a reception facility, Samos functions like a prison: crowded rooms, limited outdoor hours, and constant surveillance. When an individual’s case follows a “fast-track rejection,” fences serve as indirect pressure to sign “voluntary return” agreements, as documented by state monitoring organizations.

Field testimonies reveal constant tension, sleep disturbances, and rising depression among detainees uncertain of their duration of stay or ultimate fate. Individuals experience a form of “open-ended time,” representing a subtle form of psychological punishment. In March 2025, Amnesty International issued a public appeal to the European Commission detailing violations at Samos, including severe movement restrictions, substandard housing and services, and obstacles in accessing legal counsel, under an administrative system that renders legal objections nearly impossible within statutory deadlines.

Future Challenges

EU policy increasingly aims to establish migrant detention centers outside the Union, effectively exporting the closed-detention model to countries with limited transparency, raising ethical and political questions regarding compliance with standards when oversight is removed from European judicial and media supervision.

Detention centers remain a focal point for human rights and political challenges, where EU interests conflict with individual rights. Continuous access to reliable data—from the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture and the EUAA—is essential for evaluating policy effectiveness, analyzing the impact of prolonged detention on refugees, and providing practical recommendations to improve conditions and safeguard detainees’ rights.